No matter what we think about President Ma Ying-jeou’s opening up of Taiwan to visitors from China, one indisputable outcome of that policy is that it has created opportunities for Chinese to learn about Taiwan. For the first time, Chinese tourists, students, and businesspeople can experience Taiwan for what it is without the filters — in the education system, the media, and the political discourse — that warp Chinese perceptions on life on the other side of the ideological divide. Since the policy was implemented, millions of Chinese have visited Taiwan, thousands of them students. While this gives us reason for hope, we much nevertheless ask whether the majority of the Chinese who cross the Taiwan Strait are here to learn. In some cases, they evidently aren’t.

Before we go any further, we should perhaps draw distinctions between the different categories of Chinese who have visited Taiwan since the rules were relaxed.

The first, and by far the largest category, is that of Chinese tourists, most of whom visit Taiwan for a week or so as part of a tour group. For the most part, tour operators limit the visitors’ experiences to the usual tourist attractions — the Taipei 101 skyscraper and shopping mall, the National Palace Museum, Sun Moon Lake, Taroko Gorge, Duty Free shops, and the like. Members of those groups rarely venture out on their own, and what’s more, efforts are made to ensure that they are not “unduly” exposed to aspects of Taiwanese society that might shock them, such as street protests. As such, besides watching TV news in their hotel rooms (provided that certain channels are not blocked) or flipping through literature that is banned back home (books, pamphlets, et cetera), Chinese tourists who visit Taiwan as part of a group will have little opportunity to learn much about alternatives to the authoritarianism that exists in China. It is unlikely that they will return to their country their heads filled with ideas on how to change the system, let alone with the desire to do so.

A subset of that category is the Free Independent Traveler, or FIT, whose ability to expand the scope of his or her travels is, as the name indicates, free. However, whether FITs use this opportunity to learn about Taiwanese society and thereby come to understand the value of liberalism and democracy remains to be seen (we should also state that a number of free travelers are probably in the employ of the Chinese intelligence apparatus, as their status gives them much greater access to every sector of Taiwan). Like group travelers, FITs are also screened prior to visiting Taiwan and come only from a limited (though growing) number of cities in China. It is therefore conceivable that Chinese who are deemed susceptible to the “nefarious influences” of democracy are stopped at the gate.

Another category is that of businesspeople and investors, whose main purpose for being in Taiwan is to conduct business. As such, while they are free to move around and learn about Taiwan, their numbers are limited and like FITs it is uncertain that they have an interest in learning about Taiwan’s political system and how it contrasts with that in China. The same probably applies to Chinese journalists based in Taiwan.

The last category, and the one that for the purposes of this article matters the most, is that of Chinese students and academics. If there is any type of Chinese visitors that should give us hope, this is it. The liberal environment provided by Taiwanese universities and the duration of the students’ stay, added to their freedom to travel and to associate with their Taiwanese counterparts, make it possible for them to develop a much deeper understanding of Taiwan’s society and appreciation of its liberties. We can also hope that their young age means that their indoctrination within the closed Chinese system is less deeply ingrained and therefore can be eroded more easily.

There is no doubt that a number of those students have come to Taiwan with open minds and that they have proven amenable to genuinely learning about the place and its people. As it is now known, some of them participated in the Sunflower Movement’s occupation of the Legislative Yuan earlier this year and were invited to attend meetings held by the student leaders on the second floor of the building. Others have observed political developments in Taiwan, and more recently in Hong Kong, from the sidelines, adopting a low profile lest their activities draw the attention of “professional students” tasked with monitoring their own on campus, or that of the Public Security Bureau, which has reportedly debriefed a number of those who participated in the protests in Hong Kong. (Readers are strongly encouraged to read the open letter recently published in Asia Literary Review by an exchange student who expresses his support for the “Umbrella Revolution.” Written under a pseudonym, the letter also discusses the many reasons why a majority of young Chinese remains unwilling to oppose the Chinese Communist Party.)

A number of factors militate against the ability of open-minded students to foster change in China upon their return from Taiwan or Hong Kong. For one, the stricter political environment created by President Xi Jinping ensures that whoever tries to apply lessons learned from his or her experiences in those open societies will be quickly dispensed with. Until returning students succeed in rallying large numbers of people to their cause, they will be picked off one by one by the Chinese authorities.

Ultimately, small numbers is the problem. While liberally inclined Chinese students do manage to slip through state controls, they still represent a minority. For every Chinese student who is committed to political reform, there are three who, despite their exposure to a liberal system and receiving advanced education in Taiwan or in the West, remain stridently nationalistic and opposed to any challenge to the CCP. Others simply choose silence or acquiescence out of fear, or because doing so increases their prospects for advancement and personal enrichment through a process of co-optation.

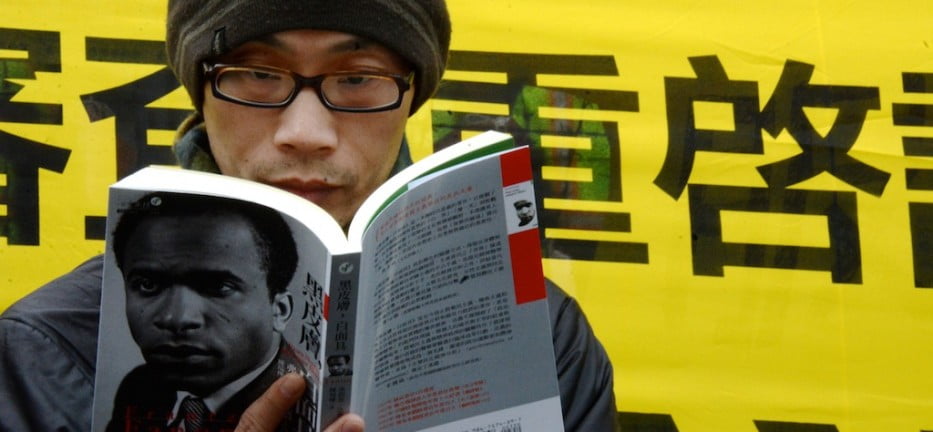

Examples abound of Chinese students who remain committed defenders of the official CCP line while abroad. Several have bullied, threatened, or followed Taiwanese students on U.S. campuses. In 2006, Chinese students at MIT sent hate mail and death threats to two faculty members (John Dower and Shigeru Miyagawa) for displaying visuals of Japanese World War II militarism in class, which they claimed had caused “emotional damage” to thousands of Chinese worldwide (journalist Louisa Lim discusses the controversy in her book The People’s Republic of Amnesia, reviewed on Thinking Taiwan last week). Chinese students abroad are also actively promoting the CCP ideology on the Internet in a bid to counter alternatives to their accepted history. They are by far the most vocal, and sometimes aggressive, at academic conferences, where they persist in trying to counter any alternative views on sensitive subjects such as Taiwan, Tibet, or Xinjiang.

Here in Taiwan, a recent dispute between a professors National Chengchi University (NCCU) in Taipei and a group of Chinese students who protested at being called “Chinese students” rather than “Mainland students” is just one of many reminders of this challenge. That particular incident, in which a Chinese exchange student made a “rude gesture” at university staff, is not isolated, and points to the possibility that despite their presence in Taiwan, some Chinese students are here not to learn, but rather to dictate and to defend the CCP’s version of reality to the hilt. The fact that CCP ideology tells them that Taiwan is part of China may also embolden Chinese students to be vocal on the subject and to be less respectful of those who hold different opinions.

The same applies to a number of Chinese academics who, inspired by a sense of superiority vis-à-vis their Taiwanese counterparts, have tended to lecture and berate rather than display a willingness to learn during academic exchanges between Taiwan and China (this author has experienced this first-hand, including one deplorable instance at a closed meeting at NCCU).

Consequently, while we should certainly encourage and whenever possible assist Chinese students in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and abroad who are open-minded and desiring to liberalize their country, we should be realistic about the possible short- to mid-term benefits of doing so. As we saw, their numbers remain far too limited, and as far as we know they have yet to find ways to organize as a group. Furthermore, the number of young Chinese who, for one reason or another, have chosen to defend the current system, remains much larger. And Mr. Xi’s CCP, which is characterized by both hubris and heightened paranoia, has redoubled its efforts to counter the activities of reformists, to such an extent that agitating against the party today would be tantamount to political suicide. We know for sure that Beijing did not permit its young people to go abroad so that they would come back to China with the goal of changing the political system. Theirs is therefore an uphill battle against extraordinary odds and a society that regards them as enemies “poisoned” by their exposure to Western values. The most we can hope for the time being is that enough Chinese students with open minds will internalize the liberal memes they came across while in Taiwan or elsewhere and activate those when the controls in China are less strict.

Whose voices are missing? The students’. You could ask students what they think, you know. As for not organizing, of course they organize, and in all kinds of ways. If you speak to Chinese students in places like Canada or the UK, you get a very interesting spectrum of ideas on Western views and their potential or lack thereof in China. But I don’t see those views here. Also, Chinese students are often participants in academic research involving questions about social change in China. I don’t know how easy it is to get a hold of such papers, but surely Google Scholar could be a good start.

Nice highlighting of a very important topic. But three comments:

1. How do you know “liberally inclined students” represent “a minority”? Do you have a particular study in mind for the assertion that only 1 of 4 Chinese mainland students who study abroad support political reform in the PRC? Otherwise, I don’t see how you CAN know this.

2. You imply both that political change in China can only come from the bottom up by those not “captured” by the system, and that there’s a stark dichotomy between “supporting the system” vs. opposing it and being “picked off one by one.” Neither of those assumptions is obvious.

If meaningful political liberalization is to occur in a highly institutionalized autocracy like China, it’s probably going to happen because moderate regime insiders want it to, not because radical outsiders force it to. And being a member of the CCP does not preclude favoring some kind of major reform of the current political system.

3. You conflate Chinese nationalism–e.g. Taiwan is part of China and always will be, and claims of that ilk–with “opposing any challenge to the CCP.” But it’s not self-evident that students holding the first view also necessarily hold the second. One could be fervently opposed to Taiwanese independence, yet still admire Taiwan’s liberal political environment and wish for the PRC to move in that direction. And if that’s the case, then this article’s extreme pessimism doesn’t seem warranted to me.

“It is therefore conceivable that Chinese who are deemed susceptible to the “nefarious influences” of democracy are stopped at the gate.”

1) I have had a friend over from China, who has been head of her university department for some time now. Our conversations went well beyond mere democracy and we had known each other well as PhD students together in the UK. If there is vetting, it probably isn’t very effective.

2) Democracy is a “nefarious influence”. What matters are individual rights and limitations on political power, which is what Hong Kong had under British rule – not the ability to vote yourself other people’s stuff via the mob, which is essentially what “democracy” boils down to as it is understood by the usual “social justice” activists.

A basic flaw of this article is that the Author assume unquestionable superiority of liberal democracy over Mainland authocracy. Not only it isn’t, but Taiwanese democracy is definitely in doldrums – starkly highlighted by two presidents one after another ending up as lame ducks with one-digit level of public support.

Furthermore, what the Author sees as a positive aspect of democracy, a typical Mainlander will usually see as its disadvantage: like streer protests disturbing daily life or election campaigns which consume time and resources which should have been spent on “real work” (a real comment of my Mainland friend who visited Taiwan during the presidential election campaign). During their short trip they will also notice that costs of life (food, shopping etc.) are higher and Taiwanese infrastructure and transportation systems are behind Mainland’s.

And finally, I believe the Author should have paid more attention to what requirements a Mainlander must meet to visit Taiwan: no one below upper middle class won’t be able to meet the requirements. Those Mainlanders who visit Taiwan are benefactors of CPC rule, they do not want a change of direction but CPC-steered progress of the current direction.

I also personally feel that Mainlanders go to Taiwan with national pride-fueled (keep in mind most of them are in their 20-40s, they saw the PRC skyrocking from an extremely poor country to the world’s second power) aggressive attitude: feeling that the Taiwanese look down on the Mainland (and the Author is the case, as I pointed out in the first part of my comment), during their time in Taiwan they tend to show off on one hand and behave in arrogant, rude way toward services staff on the other.

Mr. Cole’s article made me think back to the Chinese student at Duke who attempted to moderate between Tibetan monks and Chinese students who had came out to protest them. She received death threats and the addresses of her family members back home were posted online, they had to go into hiding.

This NY Times article from around that time (2008) describes how some Chinese students in the US reacted to a more liberal education environment. Some good points of comparison between Mr. Cole’s article and this one.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/29/education/29student.html?pagewanted=all

Mr. Cole’s article made me think back to the Chinese student at Duke who attempted to moderate between Tibetan monks and Chinese students who had came out to protest them. She received death threats and the addresses of her family members back home were posted online, they had to go into hiding.

This NY Times article from around that time (2008) describes how some Chinese students in the US reacted to a more liberal education environment. Some good points of comparison between Mr. Cole’s article and this one.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/29/education/29student.html?pagewanted=all